While I confess to some concern about making a "dud" selection, as week after week passed with few voices choosing to engage the film, I must say that the overall conversation -- between the comments and the posts -- has proven quite gratifying.

Indeed, as Chris noted in his post, my choice to offer this as a FOTMC selection derived from my interest in hearing others comment on the film as a film. I've done the kind of research on these films that Marc mentions as possibly necessary, including days and days screening the various versions in different languages released to specific markets as well as reviewing -- and producing -- variously overheated cultural studies prose about the films as ideological texts or historical documents. Yet none of that has helped me to make sense of this film as a film.

I'm gratified that some FOTMC folks have found the film(s) compelling, and not especially surprised that others have found them less than interesting. That said, I find that I'm pondering a set of questions about our disparate ways "in" to a film.

First, I wonder about the "auteur" question that Peter raised -- which I understood to be the idea that this film was multiply authored and thus defies conventional "auteurist" approaches to cinematic analysis, which presuppose a singular vision as a defining feature of cinematic composition -- and its application to Disney, or any animated production. Indeed, Walt Disney was always what we might call a "corporate" filmmaker. (I'm using the term "corporate" here in its ensemble sense, or a group of people perceived to act as a singular entity.) Though Disney himself did draw, animate, envoice, direct and produce certain productions; very early on, he "farmed" out much of the labor. So, in some ways, it seems the case of Disney also tests our limits in contemplating as an intrinsically collaborative -- indeed, "corporate" -- medium.

Second, I find that I'm wondering if the film makes more sense when considered as "experimental cinema." The value FOTMC commentators seem to have found in the film seems more in that tradition of cinema criticism, than in either film history or in more auteurist approaches. (My own background is as a cultural historian who approaches a broad array of popular culture texts through the lens of performance studies/theory, so I'm fairly unschooled in "experimental cinema" as a tradition.)

Finally, I'm struck -- after our fairly energetic consideration of such issues within

Bad Influence -- of the relative absence of commentary about "taste" in the film. A number of commentators, perhaps more than any previously chosen film, professed that Disney and/or animation more generally were just "not their cup of tea". I wonder, then, how such issues of "taste" inform the the shaping of critical vocabulary more generally.

Thanks, everyone, for being game for this/my characteristically off-kilter choice for February's Film Club. Even though the conversation wasn't huge, I found everyone's contributions clarifying to my approach to the film. What's more -- I always thought that "real" film studies types would know just what to make of this defiantly odd film. I'm now relieved to learn that it's not just me who's both completely flummoxed (and also quite fascinated) by this wackadoo little movie.

Indeed, as Chris noted in his post, my choice to offer this as a FOTMC selection derived from my interest in hearing others comment on the film as a film. I've done the kind of research on these films that Marc mentions as possibly necessary, including days and days screening the various versions in different languages released to specific markets as well as reviewing -- and producing -- variously overheated cultural studies prose about the films as ideological texts or historical documents. Yet none of that has helped me to make sense of this film as a film.

Indeed, as Chris noted in his post, my choice to offer this as a FOTMC selection derived from my interest in hearing others comment on the film as a film. I've done the kind of research on these films that Marc mentions as possibly necessary, including days and days screening the various versions in different languages released to specific markets as well as reviewing -- and producing -- variously overheated cultural studies prose about the films as ideological texts or historical documents. Yet none of that has helped me to make sense of this film as a film. I'm gratified that some FOTMC folks have found the film(s) compelling, and not especially surprised that others have found them less than interesting. That said, I find that I'm pondering a set of questions about our disparate ways "in" to a film.

I'm gratified that some FOTMC folks have found the film(s) compelling, and not especially surprised that others have found them less than interesting. That said, I find that I'm pondering a set of questions about our disparate ways "in" to a film. First, I wonder about the "auteur" question that Peter raised -- which I understood to be the idea that this film was multiply authored and thus defies conventional "auteurist" approaches to cinematic analysis, which presuppose a singular vision as a defining feature of cinematic composition -- and its application to Disney, or any animated production. Indeed, Walt Disney was always what we might call a "corporate" filmmaker. (I'm using the term "corporate" here in its ensemble sense, or a group of people perceived to act as a singular entity.) Though Disney himself did draw, animate, envoice, direct and produce certain productions; very early on, he "farmed" out much of the labor. So, in some ways, it seems the case of Disney also tests our limits in contemplating as an intrinsically collaborative -- indeed, "corporate" -- medium.

First, I wonder about the "auteur" question that Peter raised -- which I understood to be the idea that this film was multiply authored and thus defies conventional "auteurist" approaches to cinematic analysis, which presuppose a singular vision as a defining feature of cinematic composition -- and its application to Disney, or any animated production. Indeed, Walt Disney was always what we might call a "corporate" filmmaker. (I'm using the term "corporate" here in its ensemble sense, or a group of people perceived to act as a singular entity.) Though Disney himself did draw, animate, envoice, direct and produce certain productions; very early on, he "farmed" out much of the labor. So, in some ways, it seems the case of Disney also tests our limits in contemplating as an intrinsically collaborative -- indeed, "corporate" -- medium. Second, I find that I'm wondering if the film makes more sense when considered as "experimental cinema." The value FOTMC commentators seem to have found in the film seems more in that tradition of cinema criticism, than in either film history or in more auteurist approaches. (My own background is as a cultural historian who approaches a broad array of popular culture texts through the lens of performance studies/theory, so I'm fairly unschooled in "experimental cinema" as a tradition.)

Second, I find that I'm wondering if the film makes more sense when considered as "experimental cinema." The value FOTMC commentators seem to have found in the film seems more in that tradition of cinema criticism, than in either film history or in more auteurist approaches. (My own background is as a cultural historian who approaches a broad array of popular culture texts through the lens of performance studies/theory, so I'm fairly unschooled in "experimental cinema" as a tradition.) Finally, I'm struck -- after our fairly energetic consideration of such issues within Bad Influence -- of the relative absence of commentary about "taste" in the film. A number of commentators, perhaps more than any previously chosen film, professed that Disney and/or animation more generally were just "not their cup of tea". I wonder, then, how such issues of "taste" inform the the shaping of critical vocabulary more generally.

Finally, I'm struck -- after our fairly energetic consideration of such issues within Bad Influence -- of the relative absence of commentary about "taste" in the film. A number of commentators, perhaps more than any previously chosen film, professed that Disney and/or animation more generally were just "not their cup of tea". I wonder, then, how such issues of "taste" inform the the shaping of critical vocabulary more generally. Thanks, everyone, for being game for this/my characteristically off-kilter choice for February's Film Club. Even though the conversation wasn't huge, I found everyone's contributions clarifying to my approach to the film. What's more -- I always thought that "real" film studies types would know just what to make of this defiantly odd film. I'm now relieved to learn that it's not just me who's both completely flummoxed (and also quite fascinated) by this wackadoo little movie.

Thanks, everyone, for being game for this/my characteristically off-kilter choice for February's Film Club. Even though the conversation wasn't huge, I found everyone's contributions clarifying to my approach to the film. What's more -- I always thought that "real" film studies types would know just what to make of this defiantly odd film. I'm now relieved to learn that it's not just me who's both completely flummoxed (and also quite fascinated) by this wackadoo little movie.

2 comments:

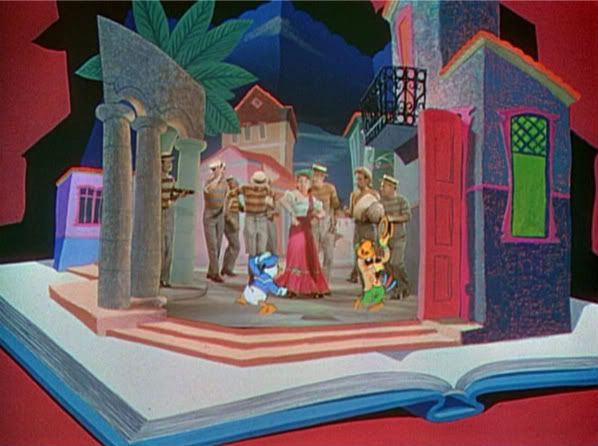

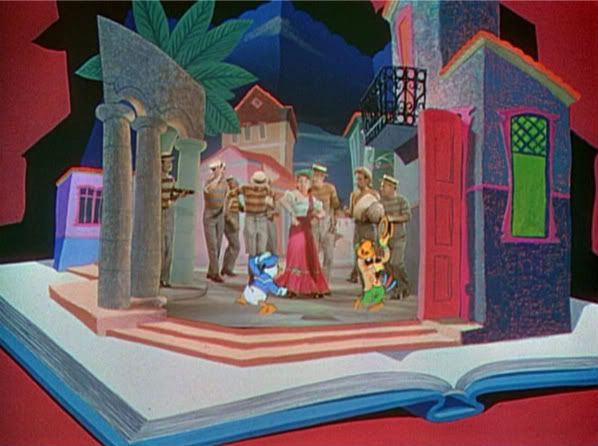

I haven't said nearly as much about this film as it deserves, but I am very pleased with the choice. It's a fascinating film - and haunting, since it is so hard to wrap your mind around. There are a lot of reasons for its difficulty, I imagine... some of them, I think, are inherent in the structure of the film itself. It's very uneven - the first half of the film, with its isolated shorts (Pablo the penguin and the flying Burro cartoon), and clunky transitions and travelogues, is particularly awkward... the middle part, with Donald and Jose, grinds a bit too, but then it takes off... It's hard to talk about it as a whole film - though I also find it hard to pull out the sections. A lot of the end of it reminded me of Busby Berkeley, for obvious reasons - but in films Berkeley contributed to, there are usually some pretty interesting progressions from one extravaganza to the next. Their abstractions as set pieces usually fit into a pattern between each other. I can't find one here... (Other than Donald getting hornier with every section. For that matter, some of the shots in this film take classic Berkeley innuendo and remove the ambiguity: those binoculars... or Donald popping through the circle of chorus girls: ouch...) In any case - the second half of the film just presents one animation showcase after another - they don't need much analysis, they are treasure chests of beauty and invention...

Yes, I'll second weepingsam.

Of all the films I've seen for the first time through Film of the Month Club, this is my favorite--which doesn't mean it's been the easiest to write about. In fact, it's been the hardest next to The Intruder, which also happens to be, in my opinion, one of the greatest movies of the last ten years. I never completed my post about The Intruder, which sits in the Drafts section of our blog and ended up becoming a different piece for Tisch Film Review about the idea of coherence. Coherence, by the way, is also a fascinating issue here, as Three Caballeros doesn't "cohere" in a traditional sense. It's travelogue, not only in the sense that it travels North across South and Central America, but that it also travels, with every episode, to different emotional and psychological parts. It was my hope to get something out on the last day of the month, but it seems we're jumping ahead to Hong, so I'll let my thoughts sit for the time being instead of forcing some kind of false cohesion on them.

Let me say that this was hardly a "dud" selection--I think it's, in fact, one of the most complicated films we've done and because of that, it's a bit daunting. To talk a little about next month's film: Hong Sang-soo is after very particular things, very aware of what he's doing, and a lot of any critical writing with a filmmaker like him consists of deciding whether or not he's succeeding at what he's attempting to do. With a movie like Three Caballeros, we're freed from that rubric and we're a little like the cat that's always scratching to be let out but then can't figure out which way is which when you finally take him outside.

Post a Comment