The scene's furiously edited montage continues with a shot of a somewhat older woman being chased by the mob, dragged into the contest unwillingly along with all the younger girls.

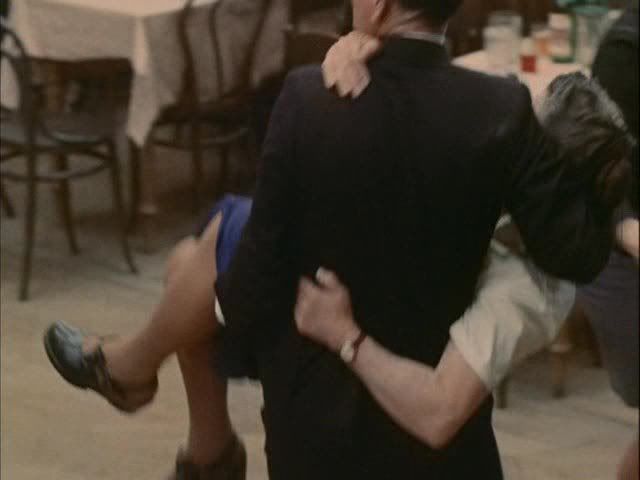

Forman then cuts to another of his shots of disconnected bodies, the heads chopped off and unseen. In this shot, the man swooping up the woman in his arms always keeps his face turned away from the camera as he spins with her. The woman's face is hinted at, glimpsed briefly from around the man's arm, which mostly obscures her from view. Individual identity is continuously deconstructed and subverted in the film, as Forman tends to view people in the abstract, as symbolic representatives of groups and ideas rather than as individuals in their own right. This deinvidualization is superficially aligned with the tenets of Communism itself, but Forman's concept of the crowd is more subtle and ambiguous. On the one hand, he stresses the dehumanizing effect of such representations, critiquing the Communist understanding of individuals — and yet his crowds are also the site of anarchic communal energy and celebration. This dialectical tension between positive and negative interpretations of "the masses" runs throughout both this scene and the film as a whole.

Another cut back to the stage, where the announcers are growing tired of waiting for the chaos to settle down — and resigning themselves to the growing certainty that it never will subside anyway. Their authority melts further away each time Forman cuts to them, as they appear more and more frazzled with each shot. The next time Forman cuts back to the stage, later in the scene, the announcers are gone altogether, and they've left the crown lying on the stage unattended. In this film, the powers in authority have essentially abdicated their right to this authority through abuse and incompetence. On one level, the film is about the (rightful) loss of faith in sources of authority and order, and the by turns liberating and destructive chaos that results.

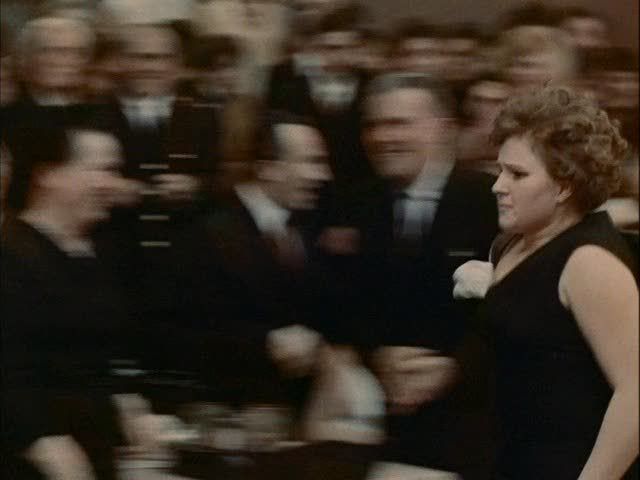

More wild fun in the crowd, a rare moment in which Forman privileges a woman's reaction amidst all this chaos, without chopping her up into her constituent parts. I'm not too sure why, but this girl at least seems to have been spared this treatment throughout the scene, as she appears several times, always with a greater than usual emphasis on her individual reaction. This is one of the elements that complicates Forman's understanding of communal representations — within his crowd scenes are reminders like this (and the shot of a girl looking out from between undifferentiated heads that I discussed in the first part of this article) that every crowd is composed of individuals, who occasionally demonstrate their individuality even in an amassed context like this.

The next three shots depict another breakdown in the scene's steadily disintegrating order. The one holdout from the beauty contest, the one girl who went up on stage — and also one of the few characters who is even given a name in this thoroughly homogenized society — finally decides to flee the stage. Earlier in the scene, her terrified, deer-in-the-headlights gaze was ambiguous, possibly caused by either the stage fright of being involved in the beauty contest to begin with, or by the confusion of the escalating riot heating up beneath the stage she's standing on. At this point, it becomes clear that her primary fear is the beauty contest itself, which places her in the public eye, probably for the first time in a culture built on crowds and groups.

Forman frames her flight with two male reactions to it. First, there's a shot of her father, who bullied her into the contest and begged the reticent firemen to include her, despite her rather obvious homeliness. His stunned, horrified reaction appears before we're quite sure what it refers to, and then in the second shot Forman traces the girl's mad dash to freedom in a stunning, rapid right-to-left tracking shot. She starts at the extreme right edge of the frame, running frantically across it as Forman's camera races to keep up with her, turning the background into a blurry smear behind her. In fleeing the spotlight, she makes herself the center of attention for a little longer, briefly the only individual singled out from the bleary crowd image. Forman follows this bravura pan with another static reaction shot, this one of the whole group of firemen, who share her father's chagrin.

This is followed by a sequence that leaves the main ballroom behind in order to trace the explosion of anarchy beyond the confines of the main room, as crowds flood out into ancillary areas and outside the meeting hall altogether. The cheerfully fleeing girls running upstairs to the ladies' room are confronted by one stern representative of the patriarchal order, in the form of the bald fireman who resolutely but vainly attempts to block the girls from running any further. The direct confrontation of the rioters with the forces of order results in victory for the forces of chaos, as they push past the fireman to get to safety. It's probably relevant, in the context of this film's theme of female sexuality, that the refuge they're seeking is an exclusively "women's only" area, one seemingly so sacred that the firemen never even think to violate it — their only recourse is to try to prevent the girls from entering the bathroom, not to enter it themselves and bring them out. This is also resonant with the obliviousness these men display about female sexuality, a cluelessness and hesitancy that borders on fear.

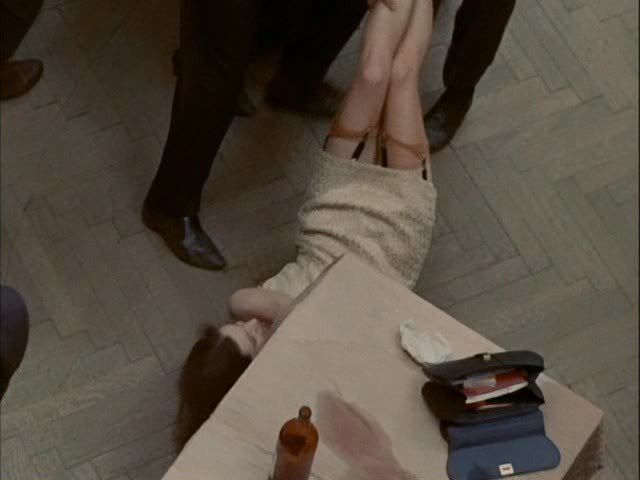

Forman then cuts back to the main ballroom, for one of my favorite shots of the film, and one that is perhaps most resonant with the subtle undercurrents of sexuality and individuality that flow through this scene. In her comments on the first part of this article, Marilyn Ferdinand mentions this later shot, saying: "Forman's peep show returns part of a woman's sexuality to her (I was particularly taken with the woman whose skirt rides up, revealing her stocking garters), but defines it in terms of the male gaze, particularly since the men are pushing the women around." This astute analysis of the forces at work here goes a long way towards clarifying what Forman is getting at in regards to Communism and the treatment of women. I think it's correct to say that Forman's sexualization of women is an attempt to free these women from the dehumanizing conformity of the mob, and that nevertheless this step towards liberation is compromised by the ogling male gaze of the firemen who judge these women by attempting to break them down. The firemen view women as assemblages of sexual characteristics, not as people, and Forman's camera frequently reflects this, commenting upon the lack of sexual and human imagination in these men. Even so, flashes of messy individuality and sexual liberation shine through: in the laughing girl carried aloft through the crowd, in the old woman who is, later in the scene, crowned beauty queen by the rioters, and in the garters that set this girl off from the anonymous crowd around her, even as she's unwillingly dragged into the mess along with them. Forman's mise en scène and framing generally confirm the prevailing anti-individualism of this culture, in order to better satirize it, but his sense for telling details continually undercuts and interrogates the assumptions of the firemen and the culture they represent.

There follows two more shots in which Forman once again drives home the profound loss of patriarchal authority in this scene. The first is a cut back to the stage which simply reveals that the announcers have departed since the last time Forman showed them, sweating and despairing. They've left the crown on the floor, amidst the wreckage of the celebration, and Forman's tight closeup on the crown is a reminder of the origination for this chaos, as well as a stand-in for the absent male presence on the stage. The second shot is another visit to the area outside the women's bathroom upstairs, where all the gathering forces of the firemen prove insufficient to coax any of the women back outside. The result is a pile-up of would-be authoritative figures outside the door, helpless to do anything other than amass themselves in an ultimately meaningless array. It's here that the firemen will, during a gap in the din, soon hear the telltale whining of a siren that calls them to action in order to fight a fire — which is, ostensibly, their whole reason for being in the first place, and at which they prove to be as inept as they are at staging a beauty contest or planning a party.

The final two shots highlighted here economically convey the essence of the scene, and of Forman's approach to this material. The shot of the crowd gathering together resolves the chaos of the preceding scene into a new sense of community, one forged from anarchic fun and destruction. Forman's wide view de-emphasizes the individual more than ever, melding each person into a whole crowd that fills almost every available inch of the screen. Just as the fleeing beauty contestants signaled the end of order as defined by the patriarchal, Communist firemen, the scene ends with the rioters crowning their own beauty queen instead, one selected from the mess of the crowd. The connotations of this moment are, in keeping with Forman's overall satirical viewpoint, somewhat ambiguous — are the rioters coming together in a meaningful way, or simply replacing the old communal order with one of their own, that merely eliminates the role of the individual in different ways?

No comments:

Post a Comment